The Wreck of the Cataraqui

On 20 April 1845 the Cataraqui ship left Liverpool with

emigrants bound for Melbourne. A quarter of the 369 passengers were from

Oxfordshire, including 42 from Tackley — the most from any village. Many

were poor families ‘encouraged’ to take

assisted emigration.

Close to its destination, on 4 August, the Cataraqui was shipwrecked

on the uninhabited King Island in the Bass Strait between Tasmania and

mainland Australia. Only nine people survived, mainly crew.

Fortunately the survivors were helped by David Howie, who was on the island

collecting animal furs. In early September they managed to attract the

attention of a passing ship, and were rescued and taken to Melbourne.

Mr Howie organised funds to return soon to King Island to bury the bodies

from the wreck in five mass graves.

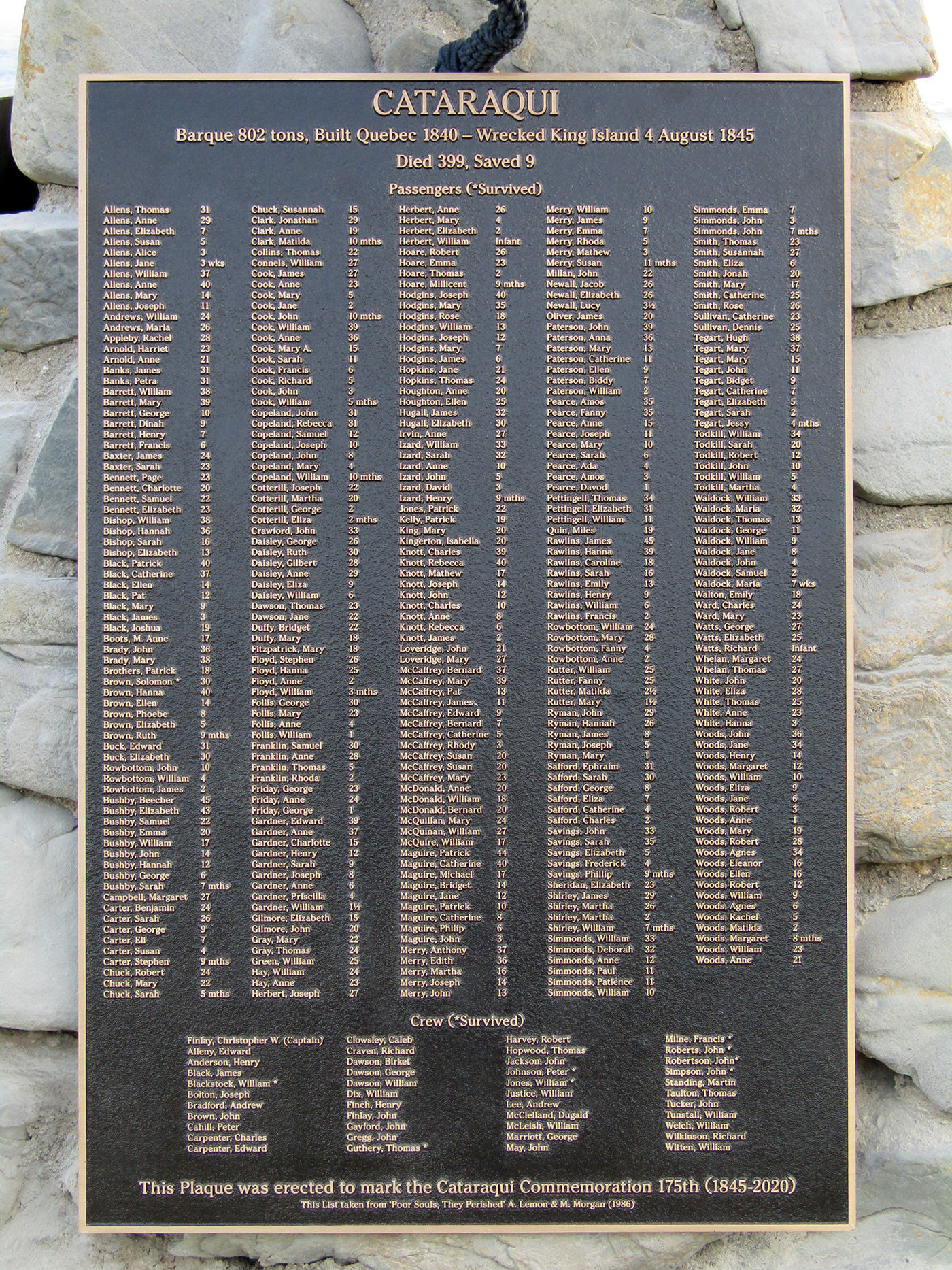

175 Years On

To mark the 175th anniversary of Australia’s worst civil maritime disaster,

on King Island a ship’s bell and a plaque with the names and ages of all 399

who died have been installed on the cairn marking the largest grave, on the

shore above the Cataraqui wreck site. On Sunday, 2 August 2020 these

were unveiled by Greta Robinson, the great-granddaughter of David Howie. The

names were read out and the bell rung for the first time.

At the King Island museum they have created a new ‘Cataraqui Room’ which

houses artefacts recovered from the ship, plus documents and pictures

related to the shipwreck. They are also restoring one of the cannons carried

by the Cataraqui, which was recovered in the 1970s from the wreck site.

Sadly, plans for commemorative activities in Tackley were prevented by the

coronavirus pandemic restrictions.

In St Nicholas’ church in Tackley,

on the ‘aumbry’ niche to the left of the altar, there’s a beautifully carved

oak door dedicated to those from the village who died in the Cataraqui

wreck. This was unveiled in February 2006 at a service marking 160 years

since news of the wreck first reached the village. It was carved by

Oxfordshire master craftsman John Bye.

There’s also an earlier vellum scroll giving the names of the local

victims, who ranged from three months to 39 years of age. This was

commissioned in the 1970s when this episode was rediscovered by Tackley

Local History Group, and was made by Kenneth Clarke.

Commemoration in 2021

It was only in the spring of 1846 that news of the wreck reached the UK

from Australia. It was first reported in London in a short account in the

Shipping and Mercantile Gazette on 31 January. Within days

the same paper had published a much fuller account which was the basis for

all later newspaper reports. By the middle of February the news had reached

all parts of the country including Oxford. On 7 February both the

Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette and Jackson’s Oxford

Journal published brief reports. The Journal and the Oxford

University and City Herald followed with longer articles on

14 February, and two weeks later the Journal published further details

on the Tackley victims.

Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette,

28 February 1846

LOSS OF THE CATARAQUE. — The wreck of this ill-fated vessel, on its way

to Australia (the particulars of which we gave three weeks since) has

occasioned much grief in the quiet village of Tackley, in this county, as

the following persons belonging to that place were among the unfortunate

sufferers: William and Hannah Bishop and two children, James and Ann Cook

and three children, William and Ann Cook and six children, Stephen and

Hannah Floyd and two children, Robert and Emma Hore and two children,

Anthony and Edith Merry and nine children, John and Hannah Ryman and three

children, John and Sarah Savings and three children, Emily Walton, William

and Deborah Simmons and seven children.

In commemoration, on Sunday, 21 February 2021 at 6:05 pm in St

Nicholas’ church, 42 funeral bell tolls were rung — one for each Tackley

villager who died in the Cataraqui shipwreck. This slow toll followed the

five-minute solo bell after the six o’clock chimes that signalled the

‘Prayer for the Nation’ throughout February to remember those who had died

from Covid. See a video

made by a visiting Blue Badge guide.

Media

History group members Rachel Strachan and Neil Wilson went to the wreck

site in 2019. Following their visit, the

King Island

Courier carried an article on the Cataraqui:

View

Download

(PDF)

Conrad Gibbens produced a film montage about the history of the Cataraqui,

which you can watch on YouTube:

A List of Emigrants from Oxfordshire

Who Died in the Wreck of the Cataraqui

From Poor Souls, They Perished: The Cataraqui, Australia’s Worst

Shipwreck, A. Lemon & M. Morgan.

Chesterton

- William Andrews (24)

- Maria Andrews (26)

Fringford

- Joseph Cotterill (22)

- Martha Cotterill (20)

- George Cotterill (2)

- Eliza Cotterill (infant)

- Thomas White (25)

- Anne White (23)

- Hanna Figge (3)

Fritwell

- William Rutter (25)

- Fanny Rutter (25)

- Matilda Rutter (2)

- Mary Rutter (1)

Great Haseley

- Charles Knott (39)

- Rebecca Knott (40)

- Matthew Knott (17)

- Joseph Knott (14)

- John Knott (12)

- Charles Knott (10)

- Anne Knott (8)

- Rebecca Knott (6)

- James Knott (2)

Kiddington

- William Simmonds (33)

- Deborah Simmonds (32)

- Mary Anne Simmonds (12)

- Paul Savings (11)

- Patience Savings (11)

- William Savings (10)

- Emma Savings (7)

- John Savings (3)

- John Simmonds (infant)

Rousham

Stoke Lyne

- John Loveridge (21)

- Mary Ann Loveridge (27)

- George Watts (27)

- Elizabeth Watts (25)

- Richard Watts (infant)

Stonesfield

- William Barrett (38)

- Mary Barrett (39)

- George Barrett (10)

- Dinah Barrett (9)

- Henry Barrett (7)

- Francis Barrett (6)

- James Oliver (20)

- James Rawlins (45)

- Hanna Rawlins (39)

- Caroline Rawlins (18)

- Sarah Rawlins (16)

- Emily Rawlins (13)

- Henry Rawlins (9)

- William Rawlins (6)

- Francis Rawlins (2)

Tackley

- James Cook (27)

- Anne Cook (23)

- Mary Cook (5)

- Jane Cook (2)

- John Cook (infant)

- William Cook (39)

- Anne Cook (36)

- Mary Ann Cook (15)

- Sarah Cook (11)

- Francis Cook (6)

- Richard Cook (5)

- John Cook (3)

- William Cook (infant)

- Stephen Floyd (26)

- Hanna Floyd (25)

- Mary Anne Floyd (2)

- William Floyd (infant)

- Robert Hoare (26)

- Emma Hoare (23)

- Thomas Hoare (2)

- Millicent Hoare (infant)

- Anthony Merry (37)

- Edith Merry (36)

- Martha Merry (16)

- Joseph Merry (14)

- John Merry (13)

- William Merry (10)

- James Merry (9)

- Emma Merry (7)

- Rhoda Merry (5)

- Mathew Merry (3)

- Susan Merry (infant)

- John Ryman (29)

- Hannah Ryman (26)

- James Harwood (8)

- Joseph Ryman (5)

- Mary Jane Ryman (infant)

- John Savings (33)

- Sarah Savings (35)

- Elizabeth Payne (5)

- Frederick Payne (4)

- Phillip Savings (infant)

Wootton

- William Bishop (38)

- Hanna Bishop (36)

- Sarah Bishop (16)

- Elizabeth Bishop (13)

Further Reading

Further information on the Cataraqui disaster and its links to Tackley can

be found in Barry McKay, Tackley to Tasmania: Pauper Emigration from

an Oxfordshire Village published by the

History Group.

See also the

King Island Historical Society Museum.

Research and text: Rachel Strachan. Modern photos:

Luke Agati (Australia); David Ginn (UK). Proofing: Anne Edwards. HTML and

map: Martin Edwards. Image accessibility: David Ginn.