Stories From Our Past

Tackley, the ‘Revolt of the Field’, Emigration to New Zealand and Another Maritime Tragedy,

1872–74

John Perkins, July 2020

The tragic story of the shipwreck of the Cataraqui off the

coast of Tasmania in 1845 with the loss of 399 lives, including 42 pauper emigrants from

Tackley, is well known in the village. Had it not been for COVID-19, this summer we would be

publicly commemorating the 175th anniversary of Australia’s worst civil maritime disaster both

here and on King Island where the emigrants lost their lives.

In early 1874, almost 30 years after the wreck of the Cataraqui, another group of impoverished

emigrants from Tackley were the victims of another maritime disaster, but en route to New

Zealand rather than Australia. Their story begins in Wootton-by-Woodstock, moves to Tackley and

then New Zealand via Plymouth and Otago, with a tragic coda in the South Atlantic and in

Shipton-under-Wychwood.

1. The ‘Revolt of the Field’

The Agricultural Labourers’ Union: Wootton and Tackley

In the spring and summer of 1872 widespread rural poverty, agricultural depression and unrest

across the country led to the foundation of the Agricultural Labourers’ Union. The movement

began in the village of Wellesbourne in Warwickshire, fifteen miles north-west of Banbury, where

the leading figure was Joseph Arch (1826–1919) and spread rapidly to other parts of the country,

including North Oxfordshire. Under the leadership of Christopher Holloway (1828–1895), who like

Joseph Arch was a farm labourer and Methodist preacher, Wootton became the centre of

agricultural unionism in the county.

The Union organised a campaign for an increase in a labourer’s weekly wage from around 12s or

14s to 16s per week, which even then would have been barely enough for a family to live on; a

fixed working week of six days with 9½ hours per day; and overtime to be paid at the rate of 4d

an hour. Holloway organised meetings in the surrounding villages. One in Wootton was reportedly

attended by 1,000 people, and labourers joined in large numbers, with Tackley the most active

village after Wootton (Oxfordshire Weekly News, 10, 17 & 24 July 1872; Witney

Express, 18 July 1872; Oxford Journal 20 July 1872).

P. H. Emerson, The Mangold Harvest, East Anglia, 1887,

British

Library

P. H. Emerson, The Mangold Harvest, East Anglia, 1887,

British

Library

The leading figure in Tackley was Jonathan Skidmore (1828–1901), an agricultural labourer. Like

Christopher Holloway, he was a Methodist preacher and his sister Hannah had married another

well-known Tackley Methodist, John Harris.

Like Holloway, Jonathan Skidmore took the campaign for the Union to neighbouring villages. On

18 May he was one of the speakers at a meeting of 200 people in Bletchingdon (Bicester

Herald, 24 May 1872), and on 2 August he presided over a much larger meeting there with

contingents from Tackley, Kirtlington, Weston-on-the-Green and Chesterton, accompanied by bands

and banners. In his speech he said that “to be chairman of such a large meeting was something to

be proud of. It was a noble work to engage in, and he believed it would have a blessed result.

No class had been so much neglected as the labourer. He earned a good living for many above

them, but was denied one for himself. But they meant to do better in future” (Oxfordshire

Weekly News, 7 August 1872).

Amid reports of the military – the yeomanry – being mobilised to bring in the harvest, the

farmers’ response was to establish the Oxfordshire Association of Agriculturalists in which two

of Tackley’s farmers, John Bulford Cooper of Old Whitehill Farm and George Gibbons of Lower

Whitehill Farm played prominent roles. The Association agreed that no member would employ a

labourer belonging to the Union or one who did not have a character reference from his previous

employer. On Wednesday, 3 July, thirteen Wootton farmers agreed to a lock-out, and by Saturday,

120 labourers there were out of work (Manchester Evening News, 12 September

1872).

Agricultural labourers in the 1870s,

TUC

Library Collections

Agricultural labourers in the 1870s,

TUC

Library Collections

Lock-out, Meetings and Marches

As the lock-out spread and support for the Union grew rapidly, a festival atmosphere, together

with a palpable sense of solidarity and hope, swept the countryside in spite of the cold, wet

summer. Meetings were attended by large numbers of women and children as well as the men.

Members of the Union wore a dark blue cockade as a sign of solidarity and defiance. In response

the farmers refused to employ anyone wearing the ‘blue’ and at a meeting of farmers in Oxford,

George Gibbons of Lower Whitehill Farm proudly reported that “there was not a man on his farm

who wore a ‘bit of blue’; they were paid off that morning” (Reading Mercury, 27

July 1782). A correspondent to the Bicester Herald (26 July 1872) offered two

versions of a song ‘The Blue Cockade’:

No. 1, to be sung by Labourers

The blue cockade

On hat displayed

Proclaims that Union men we’re made;

Of masters none of us afraid,

Nor by their looks or threats dismayed

No. 2, to be sung by Farmers

The blue cockade

On hat displayed

Proclaims what blockheads men are made

By chaps who love the “spouting” trade,

And are themselves of work afraid

Large crowds marched from village to village with banners waving, led by local drum and fife

bands. They made their presence felt. On Monday, 5 July several hundred men, women and children,

all wearing blue ribbons, marched from Wootton to Woodstock and then on to Tackley. On returning

to Wootton along the path that runs past the trig point they passed by Lower Dornford Farm

(referred to as Dornford Park Farm). The labourers had all either been locked out or had left,

leaving the farmer, Albert Wilsden, and his son to work the 400 acres on their own. At the sight

of the two of them desperately turning the hay, the procession stopped “and the band played a

lively tune, while thundering cheers were raised by the Unionists” (Oxfordshire Weekly

News, 17 July 1872).

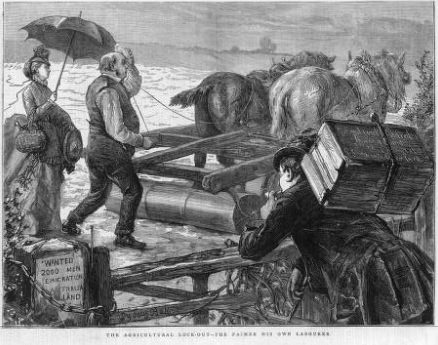

‘The Agricultural Lock-Out — The Farmer His Own Labourer’,

The Graphic, 16 May 1874

‘The Agricultural Lock-Out — The Farmer His Own Labourer’,

The Graphic, 16 May 1874

In early August more than 200 marched from Wootton and Barton to Woodstock where Holloway

addressed them in front of the Town Hall and told them that “no one wearing the ‘blue’ dared

show his face on the Shipton estate.” To show that they weren’t intimidated, the crowd marched

to Shipton-on-Cherwell and paraded down the one street in the village singing the ‘Union Song’

(Oxfordshire Weekly News, 7 August 1882).

Alongside the carnival atmosphere, there was great seriousness of purpose, dignity and

discipline. Not only did the Union refuse to be intimidated, it also refused to be intimidating

and the leadership insisted that they would always deal with the farmers “respectfully but

firmly” and would not respond to the lock-out with a strike. In part, that reflected the deep

influence of Methodism and non-conformism more generally on both its leaders and among the

labouring poor. But it was also political.

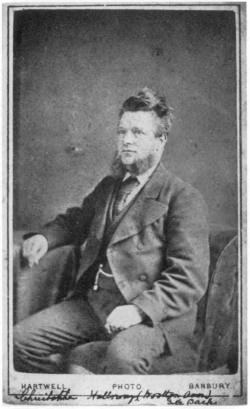

Christopher Holloway in the 1870s,

Nuffield

College, Cole Collection

Christopher Holloway in the 1870s,

Nuffield

College, Cole Collection

The largest political gathering of the Oxfordshire campaign was held in Oxford on Saturday, 20

July and reported by one newspaper under the headline ‘MONSTER MEETING OF AGRICULTURAL

LABOURERS. DEMONSTRATION AT THE MARTYRS’ MEMORIAL.’ (Oxfordshire Weekly News, 24

July 1872; see also Oxford Journal, 10 August 1872). Hundreds came from around the

county, especially from Wootton, Woodstock and Tackley, gathering in front of St Giles’ church

then marching around the city singing Union songs and ending up listening to speeches in front

of the Martyrs’ Memorial.

To applause, Holloway and others spoke of this being “a battle between capital and labour”, and

of letting “the labouring men have a revolution rather than go back to the dark ages and be

serfs and slaves of the farmers.”

“Parsons, the majority of Members of Parliament, and landowners were enemies of working men …

the Clergy wanted to persuade them to be contented and serve their masters … and the time should

come when the Churches were turned into barns and the parsons into thrashing-men.” There are

echoes here of radical 17th-century ideas of ‘the world turned upside down’.

There was widespread local support for the Union’s campaign, and not only among labourers,

their families and other villagers. The Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press (10

August 1872) reported that when the Union paraded through Oxford before the meeting at the

Martyrs’ Memorial “the sympathy of the Oxford public was with the men.” Support in Woodstock

ranged from those working in the gloving trade to shopkeepers and tradesmen, especially those

involved in Methodism. A ‘Tradesmen and Mechanics Association’ was set up in and around Wootton

whose members refused to assist the farmers and raised money for the Union. The Union raised

money from subscriptions (6d on joining and then 2d per week), from collections at meetings and

from supporters around the country. At the Martyrs’ Memorial meeting Holloway announced that he

had just returned from the Union’s head office in Leamington where he had been given between £90

and £100 (around £10,000 today) for the several hundred labourers of Tackley, Barton and

Wootton, and pledged that the Union would financially support them until Christmas if they stood

firm. In September the Union opened a cooperative shop in Wootton to serve surrounding

villages.

Defeat and Renewal

The Union campaign met with farmers’ unmoveable resistance to their demands and refusal to

employ those who were members. Union members were faced with threats that landowners would evict

them from their cottages. In August there were reports of a letter sent by the Duke of

Marlborough to all his tenants in which he proposed to transfer the cottages and allotments held

by labourers, to the farmers (Oxford Journal, 10 August 1872).

Christopher Holloway was one of the many who rented an allotment from the Blenheim estate for

16s & 8d per year. The resources of the labourers and their families were very limited; their

savings were small or nonexistent. They could not sustain a long period without work and the

Union’s funds were unable to support them until Christmas as Holloway had hoped. The campaign

collapsed and the men drifted back to work.

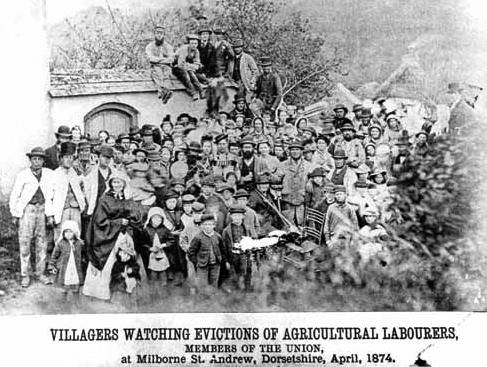

Source: Dorset County Museum

Source: Dorset County Museum

The campaign and its defeat amplified wider economic forces as well as the effects of the

continuing spread of mechanisation, including the use of steam in ploughing and threshing.

Agricultural employment became less secure. Wages were not raised. Farmers continued to refuse

to employ Union members. A year later, John Bulford Cooper who farmed Old Whitehill Farm, when

advertising for “A steady Married Man, to look after Cattle, Garden, etc.; also a Boy to look

after Nags and go to plough”, declared “No Unionist need apply” (Oxford Journal,

25 October 1873). When opportunities for other employment arose, those who could left

agriculture. This was the case with the leader of the movement in Tackley, Jonathan Skidmore.

By 1878 he was a plate-layer on the railway (Banbury Guardian, 1 August 1878),

becoming a ganger (foreman) by 1881.

In spite of defeat, Tackley remained a centre of agricultural unionism over the next two

decades. See, for example, the notices and reports of meetings in Tackley in the Bicester

Herald, 11 August 1876; Oxfordshire Weekly News, 7 February 1883;

Bicester Herald, 17 July and 9 October 1885 and 13 June 1890.

The campaign was also an education in politics. In March 1873 there was a possibility that the

government would be defeated over the Irish Education Bill and Parliament dissolved. A rumour

circulated locally that if this happened then Joseph Arch, the national leader of the Union,

would run for the Woodstock Parliamentary seat – which included Stonesfield, Tackley and Wootton

– against the incumbent Lord Randolph Churchill, father of Winston Churchill. The Banbury

Guardian (13 March 1873) commented: “As every farm labourer in these parishes who is a

householder is also an elector it may be that Mr Arch may startle the noble proprietor of

Blenheim [i.e. the Duke of Marlborough] and his tenantry.” The paper also noted that the Union

was threatening to use its political power in a local election that had much more direct

importance for labourers’ families. They might run candidates against the local tenant farmers

in the forthcoming elections to the Board of Guardians of the Union Workhouse in Woodstock where

so many of the rural poor ended their days in destitution.

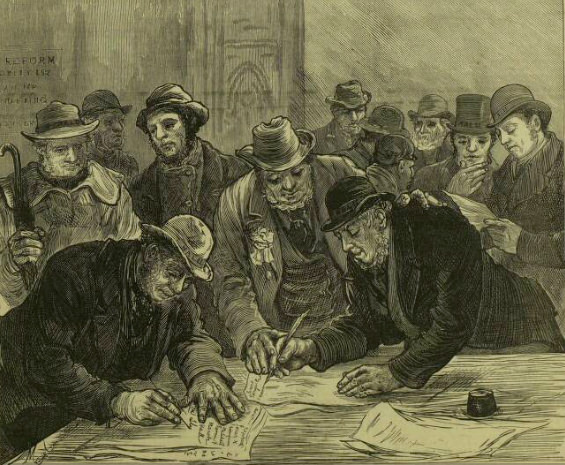

Delegates of the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union signing a petition demanding

the right to vote for rural workers, Illustrated London News, 3 June

1876

Delegates of the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union signing a petition demanding

the right to vote for rural workers, Illustrated London News, 3 June

1876

Neither outcome materialised. However, the labourers’ campaign in the summer of 1872 and the

enormous popular support it generated, together with the deep influence of Methodism, ensured

that Tackley was to be known for decades as a centre of radical politics and of support for the

Liberals. This was the case both in Parliamentary elections, especially after the extension of

the franchise in 1885 enabled most adult men to vote, and in local elections, after the Local

Government Act of 1888 established elected councils.

Once again Jonathan Skidmore mirrors these wider changes. During the Parliamentary election

campaign of October and November 1885 he chaired Liberal meetings in Tackley (Bicester

Herald, 9 October 1885). He also continued as a Methodist preacher. His wife Sarah died

in 1887 and the following year he married Hannah Colegrove who lived on Nethercote Road. They

then moved to Oxford where he died on 11 June 1901 at Sunset Cottages in St Clements, a home for

older church members, having preached for the last time, shortly before then, at an open-air

service in Tackley.

A Better Life

The collapse of the campaign for better wages and conditions led many agricultural labourers

to seek a better life either by leaving the land or by leaving their villages for opportunities

elsewhere, either in the UK or overseas.

From the start of the campaign in the early summer of 1872 the Union had sought to exploit

opportunities that labour shortages elsewhere offered, especially in the industrial regions of

the country. At a meeting in Wootton on Monday, 8 July, Christopher Holloway declared to

enthusiastic cheers that 20,000 workers were needed in Yorkshire alone and that the Union would

use its funds to enable men to move to take up these higher-paid jobs.

The Union found an ironworks near Sheffield which was willing to take on out-of-work labourers

from Oxfordshire. Within days Holloway had about forty men from Wootton who were willing to sign

up (Oxfordshire Weekly News, 17 July 1872).

The Girl I Left Behind Me

At 4:30 am, and again at 5:30 and 6:00, on Wednesday morning, 17 July, Mr Hedges sounded his

bugle in Wootton to call the villagers to bid farewell to their friends, relatives and

neighbours who were leaving for a new and better life. By six o’clock several hundred had

gathered under the elm tree in the green space in front of Holloway’s house which had been

renamed ‘Union Square’ and was decked with flags and banners for the occasion. It is still

called Union Square.

Holloway addressed the crowd, “both in joy and sorrow”, and to cheers the 40 men formed up

behind the Woodstock Drum and Fife Band. They marched out of the village to the rousing tune of

The Girl I Left Behind Me followed by a wagon and horses with the wives and children of

some of those who were going and then most of the villagers.

The hours sad I left a maid

A lingering farewell taking

Whose sighs and tears my steps delayed

I thought her heart was breaking

In hurried words her name I blest

I breathed the vows that bind me

And to my heart in anguish pressed

The girl I left behind me

‘Brighton Camp, or The Girl I Left Behind Me’ (1815) — one of many versions of the song

Half way to Kirtlington Station, at Sansom’s Gate on the Worcester to London turnpike (now the

site of Angelinos Pumping Station) the procession halted. The band turned for home and John

Banbury (1841–1911) from the well-known family of drapers and a leading figure in the Woodstock

Methodist chapel, a staunch defender of the Labourers’ Union, spoke a few words: “wishing them

‘God speed’ and every success, telling them they had right on their side, and they need not fear

the result.”

They resumed their march, crossing the Banbury Road, then down the hill, over Enslow Bridge to

the station (also called Bletchingdon or Woodstock Road). “The train soon came in, and amid hand

shaking, tears, smiles, and good bye, the party (of 74 men, women and children) proceeded on

their journey” to Sheffield and to a very different life in a large ironworks. In early August

another 50 men were reported to be ready to leave for the north (Oxfordshire Weekly

News, 24 July and 7 August 1872; Oxford Journal, 20 July 1872).

Who went to Sheffield and how did their new life turn out? We don’t know. How did they adjust

to the brutal transition from agricultural labourer to industrial worker, to the new skills

required of them, to a different social life, and to new forms of discipline and new conceptions

of time set not by the seasons and the weather but by the factory? Which ironworks did they go

to? Did they receive support from Sheffield unions and/or Methodists?

2. Emigration

From the outset the Union actively sought opportunities for emigration overseas, partly on the

grounds that this would reduce the labour supply and drive up wages. From 1872 many agricultural

labourers and their families emigrated to Brazil (unsuccessfully), Canada, Australia and, in

particular, New Zealand. Between August and November 1873 Joseph Arch went to Canada at the

Canadian government’s invitation to assess and report on its suitability for emigration from

Britain. His favourable report led to a wave of emigration: over the next few years more than

40,000 went to Canada and Australia with the Union’s support.

At the same time New Zealand was faced with a growing labour shortage. By the early summer of

the agricultural revolt it was advertising assisted places to would-be emigrants.

Oxford Journal, 6 July 1872

Oxford Journal, 6 July 1872

In spite of the assisted passage scheme the labour shortage became increasingly desperate and

after Julius Vogel became prime minister in April 1873 the New Zealand government introduced a

free passage scheme to begin in October. The hope was to get 20,000 emigrants in the following

six months. Under the scheme, emigrants would assemble at depots (i.e. warehouses) in UK ports

before embarking in order to ensure that ships sailed with full complements. The first steamers

were to sail in December in order to get labour for the coming harvest. The government was to

cooperate with the Agricultural Labourers’ Union, and Joseph Arch or his representative were to

be invited to New Zealand at the colony’s expense.

The government’s new policy had been in part prompted by a memorandum which the executive

committee of the Union sent to the New Zealand Legislative Assembly on 15 May 1873. In it,

Joseph Arch and his colleagues explained the plight of the labourers and their families, the

formation of the Union and its efforts to redress their grievances. Faced with the farmers’

resistance they argued that emigration provided a solution but that it was only possible with

proper support, above all free passage, and they offered to work with the New Zealand

government’s representatives to facilitate such a scheme.

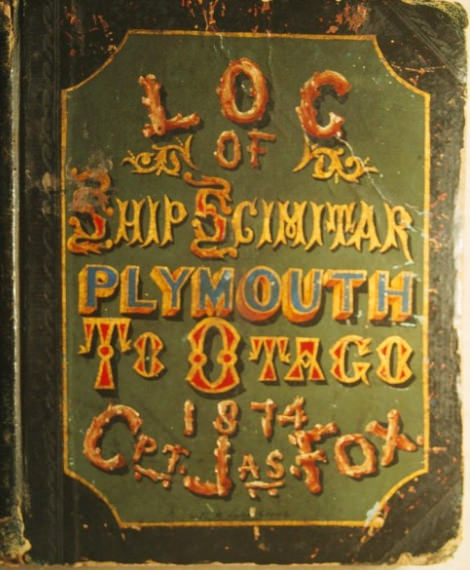

The Mongol and the Scimitar

In response to the Union’s memorandum, the government offered its full support and its

representatives in the UK made contact with the Union. The most energetic of these was C. R.

Carter and events moved very rapidly. By this time Joseph Arch was in Canada, and Carter made

contact with Christopher Holloway who invited him to a meeting of labourers in

Milton-under-Wychwood on 4 November, at the end of which eight families applied for free

passage. Holloway then proposed that he select a party of about 200 labourers and their families

and that he would travel out with them to report on the opportunities the colony offered. On 6

November, just two days later, he received a formal offer from Carter to which Holloway agreed

on the 9th while on a visit to London. He was to receive free passage, £1 a day in expenses and

his family would receive 25s a week in support while he was away. He agreed to recruit the party

in time for it to sail on the newly-built steamship SS Mongol which was due to leave

Plymouth on 15 December for Otago in order to set up a mail service between New Zealand and San

Francisco. Holloway immediately started a campaign of meetings, often held in barns or fields.

On 17 November the Union endorsed the scheme and set about encouraging it. On 29 November the

Union paper, the Labourers’ Union Chronicle, declared:

“Away, then, farm labourers, away! New Zealand is the promised land for you; and the

Moses that will lead you is ready.”

There was such a strong response that the New Zealand government chartered the sailing ship

Scimitar to leave on the same day.

The Mongol at anchor in Port Chalmers, taken by David Alexander De Maus

in 1874. Alexander Turnbull Library, New Zealand,

Ref: 1/2-015213-G

The Mongol at anchor in Port Chalmers, taken by David Alexander De Maus

in 1874. Alexander Turnbull Library, New Zealand,

Ref: 1/2-015213-G

Within two weeks the emigrants had been recruited and arrangements had been made for their

travel to Plymouth. A train was to leave Leamington station at 8:00 am on Saturday, 13

December and pick up various parties at stops between there and Didcot, including groups from

Tysoe in Warwickshire near Banbury, Wootton, and Tackley. Unfortunately we don’t know the names

of most of the emigrants on the Mongol, on which the Tackley contingent sailed, nor the villages

from which many of the others came since the Mongol’s passenger list has not survived — although

the Scimitar’s has.

The newspapers were full of stories of emigration to Canada, Australia and the US and little

attention was paid to our group beyond a few lines giving no detail (Oxfordshire Weekly

News, 17 December 1873; Banbury Advertiser, 18 December 1873; Oxford

Journal, 20 December 1873). However, a note in the Oxford Times (13 December

1873) records that a party which left Leamington a few days early was accompanied to the station

by a large group of friends. The other groups would certainly have been seen off with great

fanfare when they left.

The Scimitar, renamed the Rangitiki, being towed to Dunedin, taken by

David Alexander De Maus ca 1889. Alexander Turnbull Library, New Zealand,

Ref: 1/1-002380-G

The Scimitar, renamed the Rangitiki, being towed to Dunedin, taken by

David Alexander De Maus ca 1889. Alexander Turnbull Library, New Zealand,

Ref: 1/1-002380-G

The journey was slow and the 300 from Oxfordshire and Warwickshire did not reach the depot in

Plymouth until midnight. Both ships were delayed in London by fog and then by engine repairs to

the Mongol, and the emigrants, 700 in total including a large number of children, had to spend

nine days in crowded, damp conditions in cold, wet weather at a time when measles and scarlet

fever were widespread in the country.

The Mongol sailed on 23 December with 313 emigrants, 125 of them children, and the Scimitar the

next day with 430 including 165 children. But by then disease was on board. Both ships sailed

fast — the Mongol made the run in a record 51 days, arriving in Otago on 13 February, and the

Scimitar on 6 March, and both were quarantined when they arrived. In total 42 children died on

the voyage or in quarantine on arrival.

Source:

RootsWeb

Source:

RootsWeb

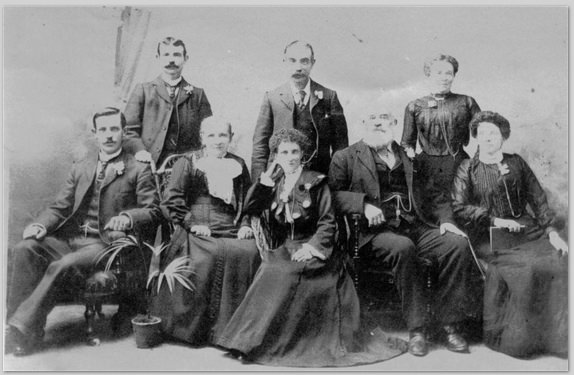

Christopher Holloway remained in New Zealand until November 1874 touring the islands. He

arrived back in London on 9 March 1875 with glowing reports of the opportunities the colony

presented — a further stimulus to emigration.

During the latter part of his nine months in New Zealand he visited some of those who had

travelled out with him on the Mongol and who had begun to establish themselves. He referred to

several of these in a letter he published in the Banbury Guardian (29 July 1875)

including John Gibbs from Tackley who had lived on The Green and who had sailed with his wife,

Elizabeth, and their six children, all of whom survived the journey. Holloway quoted one of the

letters that John sent back home. In it he writes:

“I am getting 8s a day for eight hours work, and my son, 15 years of age is getting one guinea

a week. I have bought a plot of land, and expect to have a house built upon it very shortly.”

His wage was about three times the amount that the Union had been demanding in 1872. He

eventually settled in Dunedin and the family did well as this family photograph, dated 1903–07,

shows. They had come a long way from the impoverished labouring family of 1872.

The Gibbs family. Source:

Carol Dougherty

The Gibbs family. Source:

Carol Dougherty

1845 and 1873

Comparisons between the stories of the Cataraqui disaster and those of the Mongol and Scimitar

are instructive. Those who left on the Cataraqui were identified as paupers with little or no

work and income, and were seen as a burden on the well-off in the village, living off poor

relief. Those who left in 1873 were, and saw themselves as, labouring families.

Those who emigrated in 1845 did so as a disparate group of families and individuals. Those who

emigrated in 1873 also belonged to a movement, one that had glimpsed the power that it could

collectively wield.

While both groups were driven by economic conditions and by poverty to risk emigration, those

in 1845 were virtually forced to do so by the members of the Vestry Committee, while those in

1873 did so of their own choice and with the collective support of the Union.

Of course, if there are scales of horror then the wreck of the Cataraqui with the loss of 399

lives was far worse than the loss of 40 young lives to disease on the Mongol and Scimitar.

However, a tragedy as great as that of the Cataraqui did befall inhabitants of another

Oxfordshire village, Shipton-under-Wychwood, almost two years after the Mongol and Scimitar had

sailed for New Zealand.

3. The Cospatrick, 18 November 1874

In the months and years that followed the voyages of the Mongol and Scimitar the number of

emigrants leaving for New Zealand, many of them sponsored by the Union, reached the tens of

thousands. The sailing ship Cospatrick left London on 11 September 1874 with more than

400 emigrants on board, many of them agricultural labourers and their families, four paying

passengers and 43 crew. Just after midnight on 18 November the

vessel caught fire in the

South Atlantic, seven hundred miles from the Cape of Good Hope. The lifeboats were launched,

but all except three people were drowned.

Seventeen of those who died, the families of two agricultural labourers Richard Hedges and

Henry Townsend, were from Shipton-under-Wychwood. A memorial to them stands on the village

green.

Chillingly, just as the Cataraqui is Australia’s worst civil maritime disaster, the same is

true of the Cospatrick for New Zealand.

Further Reading

- For information on Jonathan Skidmore and his family see Linda Moffat, Joan Skidmore and

Carole Skidmore,

Skidmore

and Skitmore Families of Oxfordshire, 1600–1900, especially pp. 15–16.

- J. P. D. Dunbabin, “The ‘Revolt of the Field’: the agricultural labourers’ movement in the

1870s,” Past & Present, 26 (1963), pp. 68–97.

- Pamela Horn, “Agricultural Trade Unionism and Emigration, 1872–1881,” Historical

Journal, 15 (1972), pp. 87–102.

- Pamela Horn, “Christopher Holloway: an Oxfordshire Trade Union Leader”,

Oxoniensia,

33 (1968), pp. 125–136.

- Pamela Horn, Labouring Life in the Victorian Countryside (Stroud: 1987).

- There is a lot of material on the Mongol at

NZ Bound on RootsWeb and on the

Scimitar at

RootsWeb,

including the transcript of the Court of Enquiry.

- Michael A. Beith, No Gravestones in the Ocean: The Emigrant Ship Scimitar,

1873–1874 (London: 2019).

- Charles R. Clark, Women and Children Last: the Burning of the Emigrant Ship

Cospatrick (Otago: 2006).

- Brian Gore, The Voyage of the Mongol (Wellington: 2001).

- David Hastings, Over the Mountains of the Sea: Life on the Migrant Ships,

1870–1885 (Auckland: 2006).

- Arnold Rollo, The

Farthest Promised Land: English Villagers, New Zealand Immigrants of the 1870s

(Wellington: 1981).

More Stories From Our Past